These past two weeks, I spend most of my time thinking about something that rarely gets love in blockchain discussions: state.

Not consensus.

Not networking.

Not cryptography.

State.

If the database layer is wrong, everything built on top of it is lying to you. Quietly, patiently, until one day it explodes in ways that are almost impossible to debug. I learned that the hard way in the past, so this time I slow down and treat the database as a first-class citizen.

The database layer is now complete. ZooBC uses SQLite, wrapped in C++ with proper RAII-based resource management. Simple, predictable, and extremely well understood. I am not trying to be clever here. I am trying to be correct.

Compatibility First, Then Safety

One rule guides all database work: the schema must match the Go implementation exactly.

This is non-negotiable.

Data compatibility matters. If I ever need to migrate, replay, or compare state across implementations, the tables must line up perfectly. So every column, every type, every table mirrors the original ZooBC schema.

Where the C++ version improves things is not in structure, but in safety.

Prepared statements are used everywhere. No SQL string concatenation. No dynamic query building. Every query is parameterized. Injection vulnerabilities are simply not an option.

Transactions are scoped using RAII. There is a dedicated Transaction class that begins a transaction on construction and commits automatically on destruction if everything succeeds. If anything fails along the way, the destructor rolls back. No forgotten commits. No leaked locks. No half-written state.

This alone removes an entire category of bugs that used to haunt me.

Making Database Access Explicit

Another area where the C++ version deliberately tightens the rules is row access.

Instead of loosely typed result sets, there is a Row abstraction with explicit getters: GetInt64(), GetString(), GetBlob(). Each returns a Result<T>. If a column is missing, or the type does not match, the error is explicit and unavoidable.

No silent type coercion.

No surprises.

No “this should never happen”.

The database either gives you what you asked for, or it tells you why it cannot.

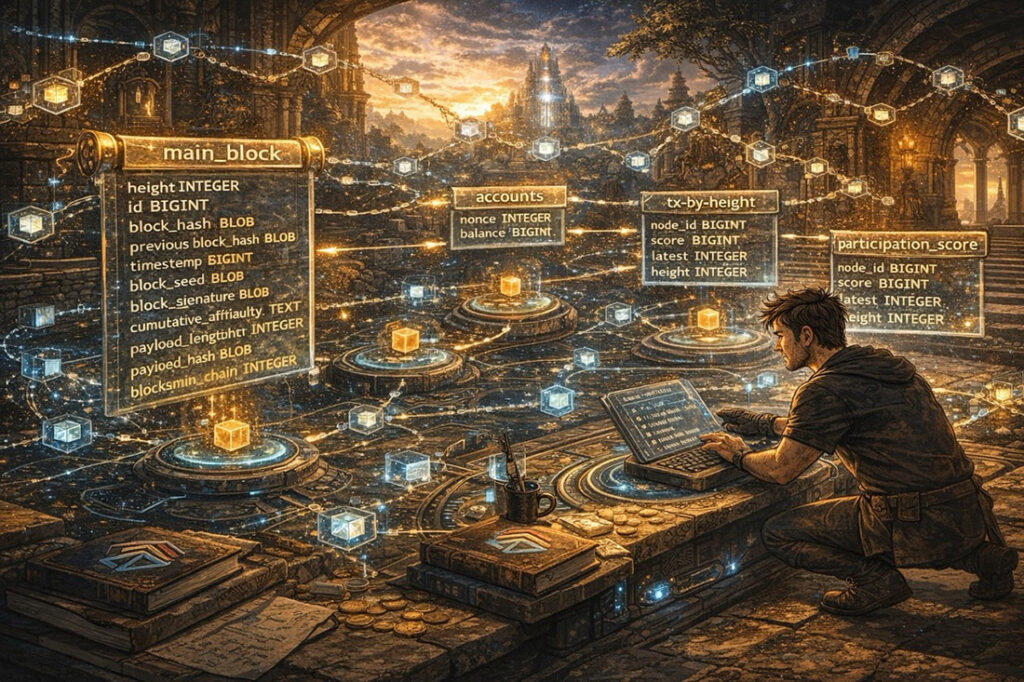

The Core Tables

Some tables deserve special attention, because they sit at the center of ZooBC’s state model.

Block storage, for example, mirrors the original blockQuery.go logic exactly:

CREATE TABLE main_block (

height INTEGER,

id BIGINT,

block_hash BLOB,

previous_block_hash BLOB,

timestamp BIGINT,

block_seed BLOB,

block_signature BLOB,

cumulative_difficulty TEXT,

payload_length INTEGER,

payload_hash BLOB,

blocksmith_public_key BLOB,

total_amount BIGINT,

total_fee BIGINT,

total_coinbase BIGINT,

version INTEGER,

merkle_root BLOB,

merkle_tree BLOB,

reference_block_height INTEGER,

is_main_chain INTEGER

);

-- Participation scores with versioned rows for rollback

CREATE TABLE participation_score (

node_id BIGINT,

score BIGINT,

latest INTEGER,

height INTEGER,

PRIMARY KEY (node_id, height)

);Nothing fancy here. Just precise, explicit storage of everything needed to reconstruct the chain.

Versioned State and Easy Rollbacks

One design choice I still genuinely like from the original ZooBC implementation is how participation scores are stored, and I keep it exactly the same.

Instead of updating rows in place, participation scores use versioned rows:

CREATE TABLE participation_score (

node_id BIGINT,

score BIGINT,

latest INTEGER,

height INTEGER,

PRIMARY KEY (node_id, height)

);Every change creates a new row. The new row is marked with latest = 1, and the previous one is marked latest = 0. State is never mutated in place.

This pattern makes rollback almost boring.

To roll back to a given height, rows above that height are deleted, and the latest flags are updated accordingly. No audit logs. No reverse diffs. No guessing what the previous value was.

The database itself becomes the history.

Quiet Confidence

There is something deeply reassuring about having the database layer finished.

No UI will ever show it.

No user will ever notice it.

And yet, everything depends on it.

Sitting in my lab, listening to the evening sounds outside, I run migration scripts again and again, drop the database, recreate it, replay state changes, roll them back, and watch everything settle exactly where it should.

State is now boring.

And that is exactly how it should be.